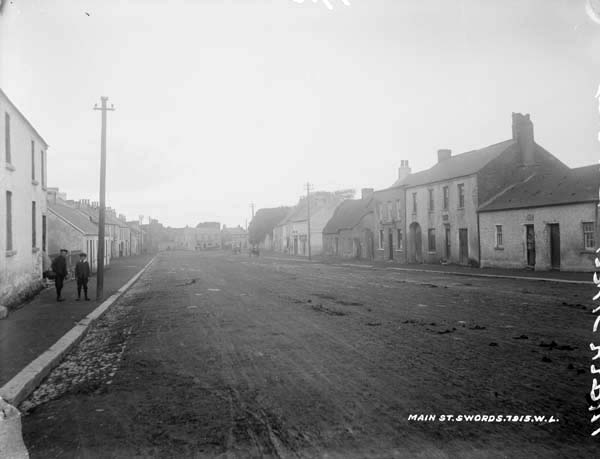

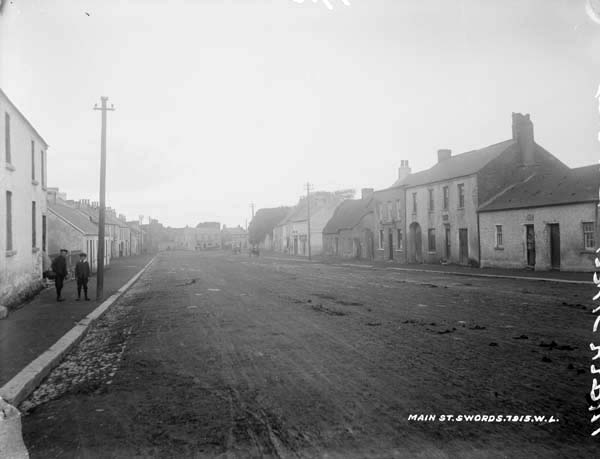

Passing through Drumcondra, Santry, and Cloghran; we enter the ancient town of Swords, consisting of a long, wide street,

situated on the great northern road, at a distance of eight miles from the metropolis. It derives its name from the Celtic

word, sord, meaning pure, originally applied to St. Colmcille's well, which from time immemorial has been one of the principal

sources of water supply in the town. This well is on the by-road to the left as we enter the village, but is now concealed

from view, a pump having been erected over it during the past few years to preserve it from contamination.

One

of the most notable events in the history of Swords is the funeral of King Brian Boru and his son Morrough, after the Battle

of Clontarf, when the bodies of these warriors were conveyed in solemn procession from Dublin, and deposited for the night

in the ancient monastery here, on the way to their final destination in Armagh.

According to the ancient records,

Swords was burnt by the Danes in 1012, 1016, 1130, 1138, 1150, and 1166 A.D.; and in 1185 it was taken and sacked by O'Melaghlin,

King of Meath. It must, consequently, have been a much more lively place of residence in those days than at the present time.

In

1578 a Royal mandate was issued for the better establishment of the Corporation of Swords, and for the purpose of determining

the limits of its franchises and liberties.

Commissioners were thereupon appointed to fix the boundaries, two

miles on every side from the town.

At the commencement of the Insurrection of 1641, the Irish army assembled

at Swords, and refusing to disperse in obedience to a warrant of the Lords Justices, Sir Charles Coote, with a considerable

force, was sent out from Dublin to attack them. He found the entrance to the town on the Dublin side strongly barricaded,

but succeeded in driving the insurgents from their positions after a sharp engagement with loss on both sides.

In

1788 Richard Talbot, of Malahide, obtained an Act of Parliament authorising him to construct a canal from Malahide to the

Broadmeadow Water through Swords for the conveyance of goods, in consequence of the prohibitive charges for carriage by land,

but the project was abandoned owing to the death of its originator.

Swords was constituted a borough by James

I, returning two members to the Irish House of Commons, and was one of the few free boroughs in Ireland (i.e., not private

property), the franchise having been vested in what were called, in the slang of the period, "Potwallopers," meaning Protestants

who had been resident for a continuous period of six months. The last two members were Francis Synge and Colonel Marcus Beresford.

The

most conspicuous objects in the town are the round tower, 75 feet high, which is the only surviving portion of the original

monastic establishment, and the mediaeval; church tower, 68 feet high, belonging to a structure which was erected not later

than the 14th century. The round tower is surmounted by a cross, placed there about 100 years ago. The adjoining modern church

was built in the early part of the last century out of the remains of the ancient one, an illustration of which latter appears

in Grose's Antiquities.

At the northern end of the street stands the ancient episcopal palace or castle, designed

as a defence against the Danes or other marauders, and sufficiently extensive to shelter the whole population of the town

and their chattels within the circuit of its formidable walls. Admission to these ruins can be obtained on application at

an adjoining house. The visitor is still shown the Constable's residence, the soldiers' quarters, and the Warder's walk, as

also "St. Colmcille's Chapel," to the right of the entrance gate, with several watch towers, one of which looking north, is in excellent preservation.

A full description of this ancient establishment is to be found in Alan's Liber Niger, and according to the inquisition recorded

therein, it would appear that the place was in a ruinous condition so early as 1326.

A short distance north

of the castle is an elevation known as Spital Hill, where, as the name indicates, there stood in ancient times a hospital,

probably for lepers - an institution to be found in every town of importance during the period when that terrible scourge

was prevalent in the country. In this connection, it should be mentioned that St. Finian, the Abbot of Swords, who was appointed

by St. Colmcille in the 6th century, was himself a sufferer from this disease, and is, in fact, usually referred to as "St.

Finian the Leper." The ecclesiastical establishment here was founded about 550 A.D. by St. Colmcille, who soon afterwards

retired in exile to lona, off the west coast of Scotland.

A mile and a quarter to the north-west of Swords are

the ruins of Glasmore Abbey, an ancient ecclesiastical establishment which was destroyed in the 7th century by the Danes who

murdered the entire community. Adjoining the ruins is St. Cronan's Well, named after the saint who fell in the massacre.

Leaving

Swords by the main road, we presently cross the Broadmeadow Water, from the bridge over which is obtained a view along the

estuary of that river towards Malahide Road. The road now passes through a dense wood - very dark in the night time - and as we ascend the height beyond Turvey bridge,

to the north may be seen Baldongan castle and the low hills of Naul and Garristown, while to the south are the dim forms of

the Dublin mountains in blue profile. We next pass the road to Skerries, branching off to the right, and continuing along

the main road, in about a quarter of a mile we reach Corduff Bridge, where we turn to the left along the road to Ballyboghil,

meeting in about a mile and a half, a grass-grown lane on the left, leading up to the site of Grace Dieu, the once-famed convent

of the Canonesses of St. Augustine.

This lane, now overgrown with weeds and brushwood, and beyond the site of

the convent passable only to pedestrians, is of great antiquity, as evidenced by its ancient red stone pavement, still visible

in places, and the old bridges by which it crosses the intervening rivulets. It can, if desired, be followed the whole way

until it reaches the main road at a distance of about a mile to the southward. The traffic along this ancient roadway must

have been considerable, the convent having been a large institution, probably in constant communication with both Swords and

Dublin. A short distance along the lane, a wooden gateway will be seen on the left, opening into a field containing a small

pile of masonry with a low doorway, the remains probably of a small chapel in connection with the establishment, and adjoining

is the ancient burial ground, long since desecrated by agricultural operations. Two horizontal tombstones still remain, one

outside the building, too worn to be decipherable, and the other inside the walls, bearing the deeply-cut inscription, "Hic

Jacet Johannes Hurley, cujus animae propitietur Dominus, Amen."; no date can be traced, but from its appearance one would

not suppose it to be more than 100 years old. The main convent building stood on the opposite side of the lane, where there

are now some very ancient walls which probably enclosed or formed portion of the original structure. A small mound will be

seen in the adjoining field marking the position of the garden, as also some large stones where, according to local tradition,

the nuns used to sit in the summertime under the shade of the trees.

Extensive orchards once surrounded the

place, and although some representatives of them still survive among the adjacent hedges, they have long since degenerated

into crab-trees, the delicate bloom of their rose-pink blossoms rendering them conspicuous objects in the springtime.

One

of the fields to the west of the lane is to the present day called "The Avenue Field," it having been traversed by the entrance

avenue to the establishment from the Brownstown road.

To the east of Grace Dieu is St. Brigit's Well, and to

the south-west, Lady Well, both of which supplied the establishment with water.

Grace Dieu was founded about

1190 by John Comyn, Archbishop of Dublin, and continued throughout its career to be maintained exclusively in the interests

of the Anglo-Norman colonists, for the education of whose daughters it was regarded as the best institution within the Pale.

In

1539, when the suppression of the monasteries in Ireland was impending, the Lord Deputy and Council intervened "for the common

weal of said land," on behalf of six important religious communities - viz., Grace Dieu, St. Mary's Abbey, Christ Church,

Connal (now Great Connell), Kenlis (Kells) and Jerpoint, representing to the English Government that in those houses commonly

and other such like, the King's Deputy and all other his Grace's Council and officers, also Irishmen and others, resorting

to the King's Deputy in their quarters, is and hath been, most commonly lodged at the cost of the said houses; also in them,

young men and children, and other both of mankind and womankind be brought up in virtue, learning and in the English tongue

and behaviour, to the great charges of the said houses, that is to say, the womankind of the whole Englishry of this land

for the more part in the said nunnery – (i.e., Grace Dieu), and the mankind in the other said houses" (State Papers,

Hen. VIII).

But greedy eyes had looked upon its fertile lands, and notwithstanding the influential memorial

to the English Government, Grace Dieu was suppressed in 1539 and granted to Sir Patrick Barnewall, who thereupon made it his

residence, the prioress, Alison White, being granted a pension of �(about � of our present money) a year, chargeable

upon the estate and some adjacent properties. The church, however, appears to have continued in use as a place of worship

up to the close of the 17th century.

There is a tradition that Turvey House, the seat of the Barnewalls, was

erected out of the materials of Grace Dien, and the complete disappearance of all the buildings of that great religious establishment

would tend to corroborate this story (see "Turvey" in next chapter).

The site stands on high ground, commanding a distant prospect of the mountains across the city smoke, as well

as a partial view of Howth.

Leaving this hallowed ground, we retrace our steps as far as the entrance to the

lane, turning to the left along a high wooded road, overlooking the flat country southward, reaching at a distance of a little

over two miles from Grace Dieu, the hamlet of Ballyboghil, the most conspicuous object in which is the fine church, bearing

the inscription - "This Church of the Assumption saved from ruin by the Rev. Francis O'Neill, P.P., 1900." A short distance

north of the village are the ruins of the ancient church, containing monuments to members of several local families. Ballyboghil

means "the town of the crozier," and it as stated by Dalton, this name originated with a crozier left by St. Patrick, formerly

exhibited in the ancient church, it would be interesting to know what has now become of this valuable relic.

Re-crossing

the bridge by which we entered the village, and taking the road at the far side parallel to the stream, in about two miles

we meet a turn to the left which conducts us to the pretty, scattered village of Oldtown, with its diminutive Catholic chapel

and neatly kept cottages, picturesque in their irregularity. As we continue our journey beyond the village, along a rather

unfrequented road, we catch a passing glimpse on the left of Malahide, Lambay and Howth in the distance across the flat tract

of country intervening between us and the sea.

At a distance of about two miles from Oldtown, we cross the Broadmeadow

Water at the entrance to Fieldstown House, in the demesne of which is an old burial ground with some remains of an ancient

church dedicated to St. Catherine. This locality derives its name from the ancient family of de la Field or Feld, who came

over to England with William the Conqueror, and obtained possession of these estates about the year 1200, retaining them until

1479, when they passed by marriage to the Barnewall family. The ancestral castle of the Counts de la Field stood in a pass

of the Vosges Mountains in France, and its lords were owners of extensive estates in both Alsace and Lorraine. Some ruins

of their ancient chateau and its chapel still remain in the Vosges - a picturesque yet melancholy memorial of this distinguished

family.

About a mile further along the road we reach Kilsallaghan, where once a hamlet clustered round the village

green, and where a fair was held in former times, while adjoining are the gloomy ruins of its castle, sheltered by tall trees,

and presenting the appearance of having been originally an extensive edifice. In 1641 this castle having been held by Lieut.-General

Byrne for the Irish army, the Earl of Ormonde was commissioned to dislodge its garrison, which he succeeded in doing after

an inconsiderable engagement. About half a mile westward of the ruin is an eminence called Gallows Hill, where, according

to tradition, one of these grim structures stood during the Cromwellian wars.

We next reach Chapelmidway, now

consisting of a few pretty cottages, with the ancient church and churchyard enclosed by trees standing upon an eminence overlooking

the hamlet. The ruin appears to be a kind of crypted appanage of the church rather than portion of the edifice itself, the

foundations of which may be traced extending eastward of the existing structure. The church, which derived its name from its

position midway between Kilsallaghan and St. Margaret's, is reported in an official "Visitation" as being in a ruinous condition

so far back as the year 1615.

Crossing the sluggish waters of the Ward River, we continue along the road for

a mile and a half to St. Margaret's which possesses no less than three churches - viz., the ancient church in ruins, the old

church now disused, and the new church, a fine handsome structure built only a few years ago. The ancient edifice, seen on

the right, approaching the village, is kept in good order, and well protected from injury or desecration by its enclosing

wall. Behind the disused church is the famous tepid well of St. Brigit, which never freezes, and is said to exhale a vapour

in winter.

From St. Margaret's a sequestered road leads to Finglas, passing on the way the dismal ruins of "The

Old Red Lion" inn, a hostelry of some note in former times, when travellers feared to risk the perils of the notorious Santry

woods after nightfall. From Finglas the excursionist may be safely left to complete his journey, according to position of

his residence.

The route described in this chapter is suitable only for cycles or motors; and the entire distance,

taking the GPO as starting point, is 31 miles. Energetic pedestrians may, perhaps, be disposed to walk it, but the character

of the country is scarcely of sufficient interest for so slow a mode of travelling.

A Little Bit Of History - The Year Is 1900

Swords is located 8 statute miles from the G.P.O. Dublin or 7 Irish miles from Dublin Castle to North Street,

Swords by the old Irish milestones. Blocks of granite 4 ft. high with the number of miles cut out in the stone.. Milestones

were placed at intervals of 1 mile.

The tram terminus of Whitehall and Drumcondra was only 6 statute miles from Swords. Nevertheless very few

walked the distance to Dublin if they had to retun, as 12 miles or more was regarded as too much. Farmers travelled by pony

and trap or outside car [hackney]. The giving of lifts was not usual unless to very intimate friends. Those who did not posess

a pony [donkeys were never used except by dealers and tinkers], availed of a passenger service.

[1] The Mail Car , one horse

[2] Savages Car Service, Swords to Dublin one horse.

[3] Caffreys Long Car to Malahide Railway Station, 2 horses.

[4] Savages Long Car, also to Malahide Railway Station, 2 horses.

The Mail Car, one horse brought the mail from Dublin each morning at about 8 am and returned to Dublin at

5 pm. Four or five passengers were carried for a price of one shilling single and one and six return. Savages car started

from Swords at 9-30 am and returned from Dublin in the evening to arrive at about 6 pm. The car stabled in Bolton Street Dublin

during the day. Bob Savage also carried parcels of goods which Swords people would ask him to buy in Dublin shops.He charged

a mall commission for the service. He carried 6 passengers as a maximum load.

Cafferys Long Car, two horses was under contract to The Great Northern Railways . The fare to Malahide was

6d single and 9d. return. The return fare from Malahide to the city was 9d.. Cafferys long car could carry 20 passengers,

full load but usually about 16 including luggage. Children went half price.

These cars, by direct road to Dublin, the mail car and savages car took one and a half hours, including

stops. The cars to Malahide Station, 3 miles, took 20 minutes, and the train jurney about 15 minutes [9 miles Malahide To

The City] There were very few bicycles until 1908. Motor cars did not appear until the 1920s. The first people in the town

to own a car were the O'Callaghns from Brackenstown.

There was a special evening mail bag conveyed by a Malahide Postman, which brought a mail bag in a pony

and cart from Malahide Station to Swords at 8.00 in the evening. He also brought the late Dublin papers. Commerical firms

in Dublin sent goods to Swords by Horse vans, and Guiness Brewary, D'arcy's brewary and Phoinex Brewary sent stout porter

and ales to the town by big special drays, drawn by draft horses. Agricultural produce was brought to The Dublin Market in

farm carts. Loadsof hay started in the early hours of the morning, sometimes before dawn, to reach the hay market in time.

The Rush market gardeners came in a long string of ponies and drays through the town in the early hours

of the morning. They halted for refreshments at The Big Tree Public House at the North end of the town which was owned by

Mark Taylor who had an all night licence to cater for these cars. On the return journey many of these farmers would be asleep

in their drays, thrusting the pony to take them home, who knew the road well.

The local people used to wake them up before they passed the R,I.C. Barracks on Main Street, as they would

be prosecuted for not being in proper control of their carts. There were no motor cars and no speed, so they were quiet safe

if they slept the whole journey. When bicycles statd to become plntyful, joung people could make more frequent visits to Dublin

and do the journey in 40 minutes instead of the one and a half hours by the horse service.

More info in the history section

|

|