James Larkin was born in Liverpool, England, on 21 January 1876, the second son of impoverished Irish parents, James Larkin (1845–87) and Mary Ann McNulty (1842–1911). He spent his childhood with his grandparents in Newry, Co. Down. When Larkin was only nine years old, he returned to Liverpool to begin work at 12½ pence per week. He was as a seaman for a while and then became a foreman on the Liverpool docks. He lost his position when he sympathised with his men. Larkin believed that the working people were being unfairly treated by their employers. He was a deeply committed socialist. He joined the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) in 1901. Five years later he was elected General Organiser, having successfully organised campaigns for Union candidates both in local and general elections. Larkin married Elizabeth Brown on 8 September 1903 in a civil ceremony in Liverpool, and they had four sons.

During the Belfast disputes of 1907 Larkin organised sympathetic workers’ strikes. He introduced the weapon of ‘blacking’ goods, whereby dockers refused to handle the goods of strike-breaking employers, and he even succeeded in bringing the police out on strike. His militant methods alarmed the NUDL, and in 1908 he was transferred to Dublin. There he reformed the Irish branch of the Independent Labour Party. Within a year he had called three strikes, in Belfast, Cork, and Dublin. He was eventually suspended by the NUDL which refused to finance his planned industrial actions. This led to his involvement in the formation of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) in 1909. This union catered for unskilled workers such as carters, dockers, labourers, and factory hands, who lived in conditions of great misery in the slums of Dublin. The ITGWU also had branches in Belfast, Derry and Drogheda. Its political programme included an eight-hour working day, provision of work for all the unemployed, and pensions for all workers at 60 years of age. In addition, it sought compulsory arbitration courts, adult suffrage, the nationalisation of the Irish transport system, and the land of Ireland for the people of Ireland. Larkin was the Union’s secretary and edited its paper, the Irish Worker and People’s Advocate.

His combination of socialism, republicanism, and trade unionism became known as ‘Larkinism’. His magnetic personality and gifted oratory soon attracted thousands to his Union. His success caused alarm and fear among the Dublin employers because he was becoming too powerful and too popular with the working class of Dublin. Larkin also organised a temperance campaign and succeeded in ending the practice of paying casual labourers in public houses.

His strike tactics alienated employers and also the leaders of the Irish Trades Union Congress (TUC). He and his Union were expelled from the TUC in 1909. In fact, his Union was not re-affiliated until 1911 and shortly after that he became president of the TUC. In June 1910 he was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment on a charge of misappropriating Cork dockers’ money while working for the NUDL (at most he was guilty of sloppy accounting and not of embezzlement). He was released on 1 October 1910, following a petition from the Dublin Trades’ Council to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl of Aberdeen. From 1911 on he attacked the Dublin employers in the Irish Worker. In 1912 he joined with James Connolly in forming the Irish Labour Party. Later that year he won a seat on Dublin Corporation, but he was removed after a month.

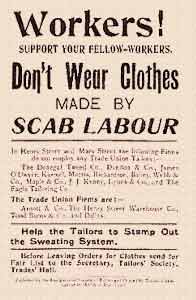

Larkin led a series of strikes involving carters, dockers, railwaymen, and tram workers in the city, and the employers, led by William Martin Murphy, were spurred to action. In 1913, the employers decided to demolish Larkin’s Union. Murphy was the owner of the Irish Independent, the Irish Catholic newspapers and Clery’s Department store, and he was director of the Dublin United Tramway Company. Murphy demanded that his workers sign a pledge to remain loyal to their employers. When the workers refused, the great Lock-Out of 1913 followed. Other Unions supported their fellow-workers and about 100,000 were thrown out of employment. Despite being reduced to starvation, the workers, under Larkin’s leadership, kept up their struggle for eight months, and although the result was in Connolly words ‘a drawn battle’, the workers had won the right to fair employment. Because of his involvement in the strike Larkin was sent to prison for seven months but was later released after protest meetings were held in England. Although £150,000, in money and food, came from the British labour movement, a British Trades Union Congress meeting in Decemeber 1913 overwhelmingly rejected Larkin’s proposal for a general strike in Britain.After 1914 Larkin’s Union was low in numbers and funds.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Larkin called on Irishmen not to become involved. In the Irish Worker he wrote: ‘stop at home, arm for Ireland, fight for Ireland and no other land’. He also organised large anti-war demonstrations in Dublin. In October he went on a lecture tour of the USA to raise funds, leaving the management of the ITGWU in the hands of James Connolly and William O’Brien. His visit to the USA became a nine-year stay. He involved himself in the American labour movement, the International Workers of the World movement, and was a delegate to the founding convention of the American Communist Party. He lacked the money to return home and was eventually arrested and imprisoned for his trade union activity. During his imprisonment he was annually re-elected general secretary of the ITWGU. From his prison cell he denounced the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Pardoned in 1923 by the governor of New York, Alfred E. Smith, Larkin was deported to Ireland.

He returned to a different Ireland but nevertheless he got a hero’s welcome. He failed to regain control of the ITWGU. He later argued that it was not working hard enough for worker’s rights. The Union disagreed, and in 1924 they expelled Larkin. With his brother Peter, he founded the Workers’ Union of Ireland. He secured recognition from the Communist International in 1924. He visited Russia as representative of the Irish Section of the Fifth Congress of the Third International, or Comintern.

Larkin returned to the Labour Party again after securing amendments to the Trade Union Act of 1941. He served on the Dublin Trades Council and became a Dublin city councillor and a deputy in Dáil Éireann from 1927 to 1932 and again from 1943 to 1944. His last big success was to win a fortnight’s holiday for manual workers following a fourteen-week strike. Larkin, ‘friend of the workers’, died in Dublin on 30 January 1947 and was buried at Glasnevin. A statue of him by the sculptor Oisín Kelly now stands in College Green in Dublin.

Biography & Studies. Donal Nevin (ed), Jim Larkin and the Dublin Lock-Out (Dublin 1964. Emmet Larkin, James Larkin: Irish labour leader, 1876–1947 (London 1965; repr. London 1989). John Gray, City in revolt: James Larkin and the Belfast dock strike of 1907 (Belfast 1985). Emmet O’Connor, A Labour history of Ireland, 1824–1960 (Dublin 1992). Donal Nevin (ed), James Larkin, lion of the fold (Dublin 1998). Emmet O’Connor, James Larkin (Cork 2002). Pádraig Yeates, Lockout: Dublin 1913 (Dublin 2000). Joseph Deasy, Fiery cross: the story of Jim Larkin, with new introduction by Francis Devine & Niamh Puirséil (2nd ed. Dublin 2004).

Tomás O’Riordan